Introduction

Body Echoes explores the combination of Virtual Reality and Dance with the aim of creating a performance, based on collaborative self-expression. The project studies a range of possibilities for multiple people to embody a single being in VR. In correlation, it investigates multiple perspectives for audience engagement. Creative Industry Fund NL granted us a start-up grant as part of the digital culture fund in The Netherlands.

Who are we?

Body Echoes is a cross-disciplinary project that was explored by a diverse team. Nikita Kayal, and Roger ter Heide are VR experts, designers, and explorers that like to connect different mediums of expression. Doron Hirsch, is a designer and choreographer with experience in new form performances, integrating performance and spatial installations. Maria Mavridou is a contemporary dancer, who is working internationally, developing solo work and collaborating with artists from the field of dance, performance, music and visual arts. Kenzo Kusuda is a Japanese choreographer/dancer, who reveals the poetry of the dancing body and takes the audience to a world filled with imagination.

How did Body Echoes start?

When we started Body Echoes, we were already exploring multiple concepts around embodiment, and finishing our research project, Kinesics on using body language in VR. This interest and a chance conversation with Doron Hirsch inspired us to define a new journey of further exploring embodiment and ideas on shared embodiment with dancers.

In an early test with one of our existing prototypes with a dancer, we delved into interesting conversations around what they could feel with their body and how it was connected to the virtual space. They especially liked the part of losing the physical boundaries, of being able to experience and react to sharing space with another dancer that was not possible otherwise. They went through each other’s virtual bodies and explored interactions that were only possible in VR.

With the dancer’s insight and language of how their virtual body connects to their physical one, our passions in exploring the realms of virtual reality led to the vision of combined virtual performance and art exploration. So the stage was set.

What did we explore?

Our story is split into three sections:

- The experience of embodiment for dancers: as a snake, as a combined human embodiment, and what happens when the audience participates within VR.

- The possibilities of mimicking and puppeteering: creating a realm of snakes, humanoid dancers, or a Medusa.

- The making of Body Echoes: our initial prototypes, the challenges of controlling a non-humanoid body and obtaining self-awareness, and the opportunities and challenges encountered with standard VR headsets.

We would like to invite you to our journey. Covid-19 did influence that journey in terms of timing and concerns of working together in a closed space. However, it also showed us how you can share a creative space together through an online connection. A number of our trial sessions were done with participants around the world from elsewhere in the Netherlands to Berlin and Vancouver.

Part 1

The experience of embodiment for dancers

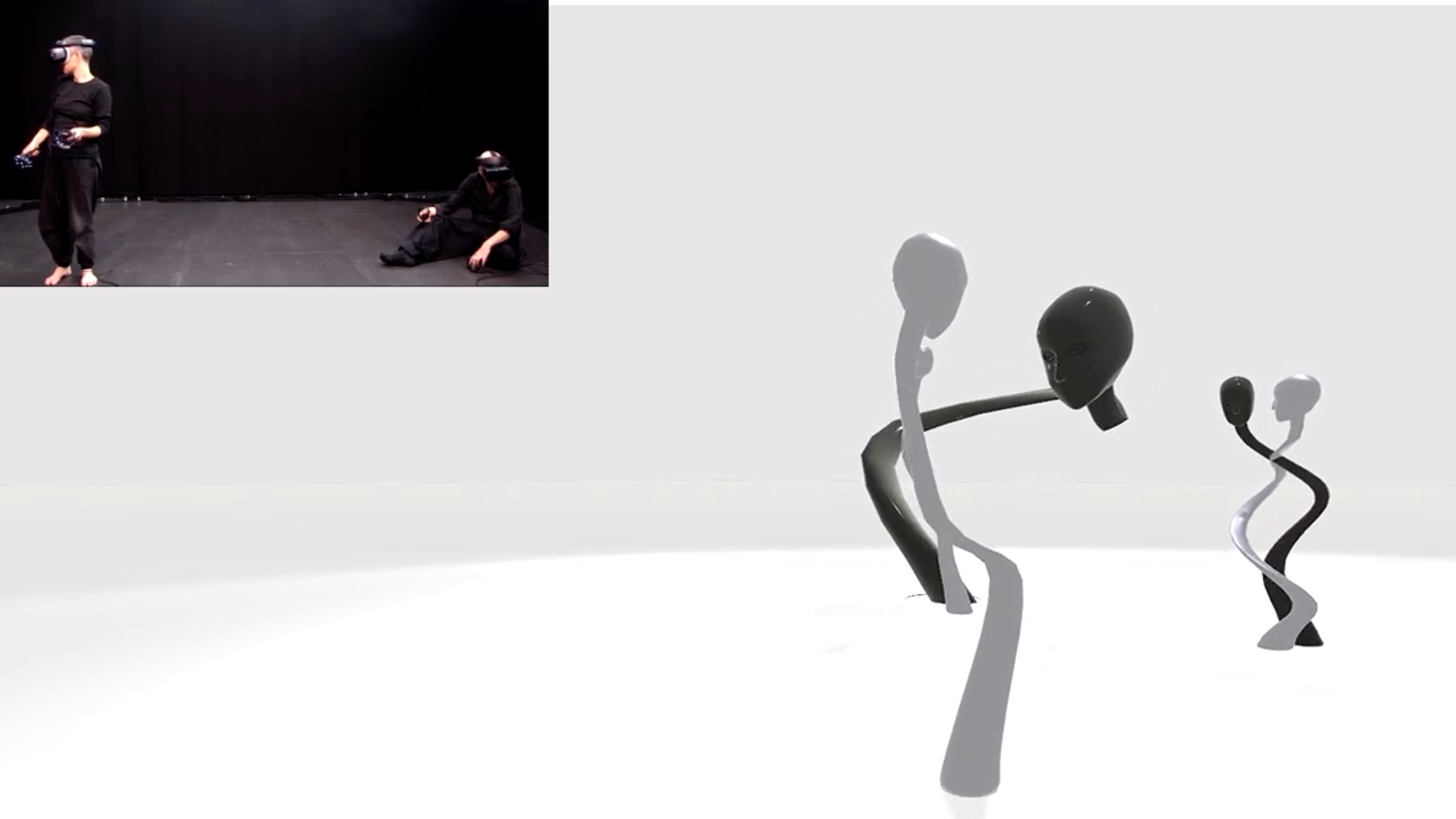

Body Echoes is about how dancers react to each other in a Virtual Reality environment when confronted with different embodiments. We experimented with several prototypes. You can read more about this process in our “Making of Body Echoes” chapter. Here we will focus on the two types of embodiment we tried with the dancers: a non-human snake body with a humanoid head, and a humanoid figure with extendable arms. We explored these both as single bodies and multiple bodies. We also explored, as part of the online edition of A.Maze 2020, what happens when we allow audience members to join the dancers in VR.

Non-Human embodiment – Snakes

In our snakelike figure, the head was directly controlled by the head position of the dancer. The rest of the body was controlled by the VR hand controllers, determining the position in spaces, the curving, and the coiling. The comfort the dancers reached with the use of VR technology evolved in the first couple of sessions. At first, they needed to understand how their hand movements influenced their body. Movements were big and a mirror was helpful to provide feedback.

Once we got past that, it was joyful to watch dancers use the embodiment to explore new forms of expression and creation that went beyond our original designs. With the comfort of their embodiment came the freedom to explore the possibilities. The curiosity to explore small motions and different feelings of closeness. As the snake body is much thinner than a human body, the way the two bodies can entangle is in a much smaller space than normally possible. This creates new feelings of closeness.

So the dancers also played with where they placed the controllers. One of the dancers chose to wear the controllers up his arm and then use his free hand to touch the virtual avatar of the other dancer. This was a beautiful moment of immersion and we still seek to find answers on how best to capture such moments to share with the audience in a performance.

We also explored how our scale can change the experience. Physically our bodies define scale but in VR we can change this. Interacting with a much bigger or smaller snake redefined the relationship the dancers had with each other from humbleness to a feeling of care or power.

We then took it one step further, can you have a feeling of shared embodiment? Can you let go of control of part of your body or get the feeling of a combined body? For this, we looked at snake clusters that were a combination of your own snake and that of the other dancer. This was interesting but confusing as to where to look and whom to interact with. We will explain more on this topic in our chapter on mimicking and puppeteering. There was also a reason why the snake did not support a feeling of combined embodiment. It lacked the mass, the substance for the bodies to easily intersect and in that way blur the boundaries between bodies.

Exploring combined embodiment – the Torso’s

We wanted a humanoid figure that was recognizable, but that could somehow extend the possibilities of reality. Our core goal was however what happens when the bodies of the two dancers start to overlap.

Tilted planes

As an initial experiment, we tried changing perspectives by warping the sense of space. In the virtual space, the dancer could feel as if the other dancer is on the wall. This perpendicular relationship created intimate moments and interactions unique to VR, with bodies intersecting or the ways bodies could face each other and move. The hands of the avatar could be extended, this enabled the dancers to also change the reach of their interaction.

It was sometimes very difficult for the dancers to make sense of what they were interacting with. From a first-person perspective, It was difficult to perceive how the bodies were intersecting because the space was compact. Without a mirror, it was also difficult to understand what it looked like from a distance.

This gave us ideas for what might be meaningful in order to explore shared embodiment.

We decided to look at a combination where there would be less confusion caused by the intersection of bodies but focus on the interaction between bodies in our combined torso experiment.

Combined Torsos

Our last experiment in this phase was a set of combined torsos. We decided on a set of 3 torsos that were coupled. The torsos were stuck in position at the pelvis. The top torso was directly controlled by a dancer. Of the other two, one was mimicking the other dancer, and one was mimicking your own avatar. The other dancer had a similar configuration. These two sets of three torsos were placed next to each other as you can see in the image. There were moments when the dancers tried to reach out and interact with one of the bodies, and initially, they found them reacting very similarly only to realize that the torso was a copy of their avatar. The ambiguity of whose body is it, and if the interaction is with the other or me created this magical moment of shared embodiment.

Some feedback we got is that the dancers would like to see if they could the other embodiments could be slowly introduced. This would make them less anxious about all the possible angles and movements possible with the combined torsos.

Audience perspective

At the online edition of A.Maze 2020, we shared our progress with a small online audience. We organized a live stream and invited participants to join in VR.

The audience members had the same exact snake embodiment except that they were grey instead of the black snakes for the dancers. We had only communicated to the audience how they can use the controls and the fact that they would be in the experience with professional dancers.

Initially, almost all the audience members explored their snake by swinging their hands around to try out the movement of the snake. Slowly, by following the lead of the dancers, the mood of the movement changed. Some audience members started to come up close and be a part of the performance. Others chose to stay slightly away and just be a viewer from different perspectives.

Once they had the same body, the question of how to create those forms was interesting to ponder. Were the dancers lying on the floor? How much time have they spent embodying these snakes?

Most participants admitted having a learning curve to adapt to their new embodiment. One of them wished to have a more gradual transition to a non-human snake so that they could get more time to adapt to their new body.

Almost all the audience members found the experience to be very intimate, even though they were in different parts of Europe or even on another continent and had no clue who the other people were. Our snakes did not suggest a gender. This influenced some audience members on how they addressed the dancers.

The perspective inside VR led to more questions about what their role is during the performance, do they need to participate, and if so, how? Is there a sacred space or a stage that I, as a viewer, am not allowed to enter? What is their relationship with the other audience members? Do we set rules, or create and explore them by reading the movements of others?

We also had the option to change the scale of the dancers. The dancers could become really big with respect to the audience members. This changed the power dynamics significantly, and in some ways, could also relieve a nervous audience member, whose movement didn’t have the same impact on the overall performance. It changed the relationship of how the snakes were viewed as well. The projections changed from that of equals to a parent-child one.

We see that inviting the viewer into VR has a lot of promise. It offers a very unique experience to even those who engage with VR and performance in their daily life. And we have only provided a peek of the experience we might provide to a VR audience.

The VR experience was of course not the only way for an audience to enjoy the performance. Everything we have been showing here has been a 2D view of the virtual embodiment from different camera perspectives. But it is not just the projection in the virtual world that intrigues. In many cases, the exploration of the dancers in the real world is just as interesting. How does their perception of the virtual world change the way they move their body, or explore the world? How can someone lying on the floor lead to an upright dancing snake? Using your hands to explore space, even if they have no projection in the Virtual world can still feel intimate, because of the choices the dancers make. Some audience members have indicated they even prefer to watch the dancers instead of the projection. This is interesting to further consider as it opens up possibilities to offer different perspectives on the same performance and does not require everyone to have a VR headset.

Future Possibilities

We are currently connecting to dancers, production companies, and others to see how we can make the step from experiment to performance with Body Echoes.

The limitations presented by the current times of social distances have also shown us that there are more possibilities for remote experiences that go beyond a live video performance.

There are many ideas, variations, and stories we would like to tell, visualize, embody and put to music. Many partners we would like to include in our explorations. Our journey has just started. Would you like to join?

Part 2

Mimicking and Puppeteering

Our research showed us that embodiment and mimicking can lead to interesting new forms, creating interesting patterns by just mimicking an initial form. However, in evaluating the experience with the dancers we also discovered that what is visually intriguing may differ from what is interesting in terms of immersion and interaction. We will share more on this in this chapter.

Medusa

We had initial ideas on making a form like Medusa. The medusa had three different types of embodiment:

One, where both the players controlled multiple snakes on top of a Medusa’s head. The head itself was static.

In the second, one player controlled a human body, and the other player-controlled the snakes sprouting on the head.

In the third embodiment, one player was controlling a giant human head, with most of the body hidden below the floor. The player could however move their hands above the floor.

All these embodiments were such that the dancer had a third-person perspective of both the snakes and the humanoid shape. So the players themselves are able to see the Medusa from different angles. We chose a 3rd-person perspective to enable the dancers to see the effect of their movements. Being a snake on top of a moving head was certainly not an option as this would cause motion sickness.

Overall, Medusa had great visual appeal for a person viewing the imagery. But it offered little depth in terms of the possibility of exploration and the movement of the dancers. The moments where the hands could come out of the floor was interesting and gave us more ideas to play with scale. Another learning point was when the dancers had asymmetric roles, one human, one snake, the dancer playing the snake felt their movements become insignificant. This was due to the fact that the movement of the human-like avatar player was much bigger. This helped us think about the audience’s perspective and also narrow down how we wanted to move forward.

Medusa is an interesting concept in visual storytelling, but not necessarily in the space of dance and interaction.

Multiple humanoid avatars projections

We added multiple humanoid avatars that followed the movement of the two dancers. In our first attempts, we placed a large number of avatars in the scene and the dancers could move around them and see them and their overall forms from different viewpoints.

One of the dancers found the experience to have much too many perspectives. It felt confusing and exhausting as there was no natural choice to focus on, out of the many perspectives offered. When we tried other multiple-body projection ideas, we took this into account by limiting the copies to a much smaller number.

This experience gave us insight into how the role of third-person puppeteering control differs from the experience of embodiment from the first-person view. While we continued our journey with mimicking and projecting the movement to more than one body, we became more aware of the importance of an experience in first person embodiment. For Medusa, the role of the dancer was primarily puppeteering with limited possibility to improvise and respond and interact directly with the other dancer. So when looking at further combined embodiments we emphasized the direct interaction between dancers.

Multiple Snake Configurations

In this setting, we created additional snakes at the base of each dancer’s snake. The newly spawned snakes were not created next to yourself but next to the other dancer’s snake. Each “baby” snake followed the movement of the creator who spawned them. This created two body-of-bodies, a central snake surrounded by a collection of snakes controlled by the other dancer. It is visually interesting. The dancers had a desire for more control over when, where, and how many baby snakes could be spawned. In this example, the baby snakes could only be spawned in a fixed position in relation to the dancers and were limited to 5 in number and maximum size.

The interaction with the babies felt limited. Being a projection of the other dancer, it limited the possibilities for improvisation, as the copy had no direct awareness of your movements, and how they related to their own.

A next step could be to explore more control and a dynamic approach to the creation of new snakes, adding composition and storytelling elements as the world is inhabited by more and more snakes. Another idea was to have a lot of snakes and let the dancer embody different ones at different points in times. So in the experience, they could view and control the world from different perspectives. These are ideas we might want to still explore in the future but they were beyond the scope of the current phase of Body Echoes.

Part 3

The Making of Body Echoes

Brainstorm and Initial Ideas

After an initial brainstorming for ideas on different kinds of embodiments, we started prototyping a couple of them. While we did have some ideas for a humanoid avatar, we decided to try out the non-humanoid forms first.

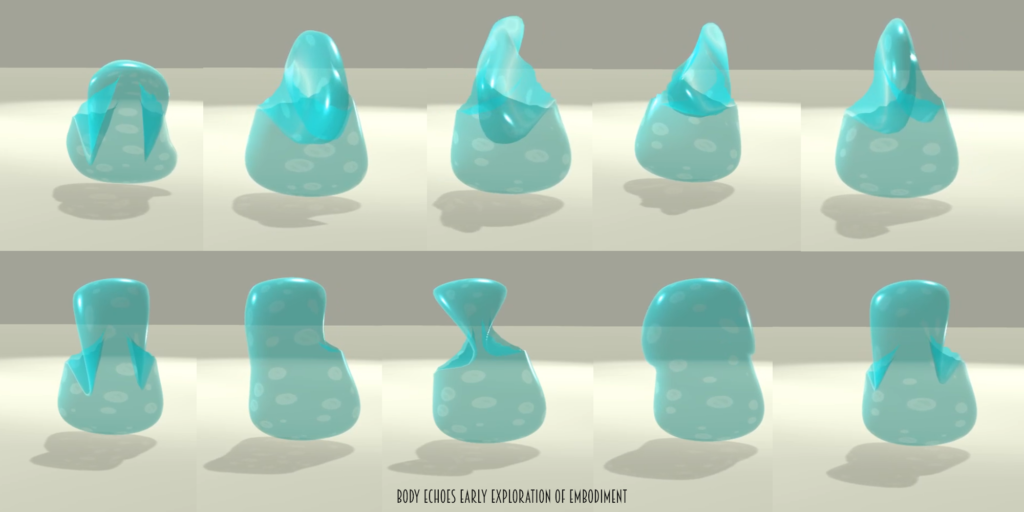

One of the forms was a snake-like form with a human head. The snake-like form was adapted from some initial sketches we had made with inspiration from sculptures by Emil Alzamora. The other form was a blob that could change its shape based on the input of the headset and the controllers.

Some interesting insights were gathered during an initial evaluation with Doron Hirsch the choreographer.

The Blob

What we had imagined was an expanding and fluid blob form that changed into different movements and patterns.

A moving sculpture of sorts. The idea was to embody this separately or together.

With some testing with Doron, we quickly realized that you couldn’t experience much of your own body or that of the other person. Your own avatar wasn’t visible without the help of a mirror. It was very difficult to get the fluidity we wanted. We realized if we wanted a completely free-form, we would need to spend a lot of time developing a responsive mesh system before being able to test anything. This was beyond the scope of this project.

This prototype had many restrictions. It could only take some specific forms and the variations weren’t too high. With the challenges we still had we decided not to further pursue this prototype.

The Snake Figure

The initial tests for a snake-like figure with a human head started with a snail-like bottom. In our limited first tests, we could see that there is potential to explore more. We came up with more options to both refine the embodiment, as well as derive complex embodiments from it.

With the snake, the head follows your head in all 3 dimensions. The left controller moved the top part of the stem of the body, the right controller moved the bottom part of the stem and also allowed you to slither around the base of the figure.

The snake-body evolved over time. We lost the slithering snail-base since that wasn’t giving too many affordances for movement, but was defining a large part of the form. We also added a way to coil the snake’s body, and allow the dancer to control the amount of coiling.

We tested this with the dancers. What was interesting was observing the adaption of the dancers to slowly embody the snake-avatars.

Humanoid figure and extended hands

Another form we worked on were human figures who could extend their hands. The human figures themselves had only the three points tracked, by the headset and controls of a standard VR headset. The leg positions were approximated. This did give a feeling of limited control by the dancers compared to what a full motion-capture suit could offer. But we had several reasons to explore the possibilities with just a commercial headset with no special add-ons, so we decided to stick to our approach.

Mirrors and self-awareness

Mirror – A mirror was an essential component to enable the dancers to get familiar with and understand their new embodiments. The dancers needed multiple sessions using the snake avatar to feel the embodiment and be able to naturally move the snake with their bodies.

Once this was achieved, they started to step away from the mirror. It was initially a necessity to have the mirror. But it also could limit the interaction with the other dancer, when the dancer’s gaze is fixated on the mirror.

We also had the possibility to make copies of your avatar that we placed in your line of sight, and thus a 3d mirror of sorts. But the 3d copies don’t give you the same (simplified) perspective as a mirror. Your relationship and your viewing angle could make it difficult to understand the form and to understand what that movement means for your own body. We saw that similar thing whenever we added multiple copies of the avatar. Maybe, it also had to do with the fact that a puppet of your avatar occupied space of its own whereas the mirror we know is merely a reflection of ourselves.

Standard VR controls

We had initially planned to add more sensors to enable fuller body tracking. We were looking at sensors for legs, feet, and chest. But with them came a lot of additional challenges to make it work. We decided we would rather spend that time on artistic exploration within the given limitations, and focussed on the standard 3-point tracking.

When we started exploring ideas with the snake and the connected torsos, we found that there is so much to be explored regardless of limitations. One of the interesting things was that the avatar’s pose was not a direct copy of that of the dancers. This gave to interesting moments of watching both the image on the screen and looking at how the dancer’s created those bodies. We had a dancer leave the controller on the floor and extend his snake to a much bigger snake than that was humanly possible. We found that we could explore that would not have easily been touched if we would have tried to create an exact projection.

We also figured out that using a standard VR headset could help engage a larger audience in VR. If everyone needed full-body tracking, we would not have been able to explore the possibility to bring the audience into the VR world.